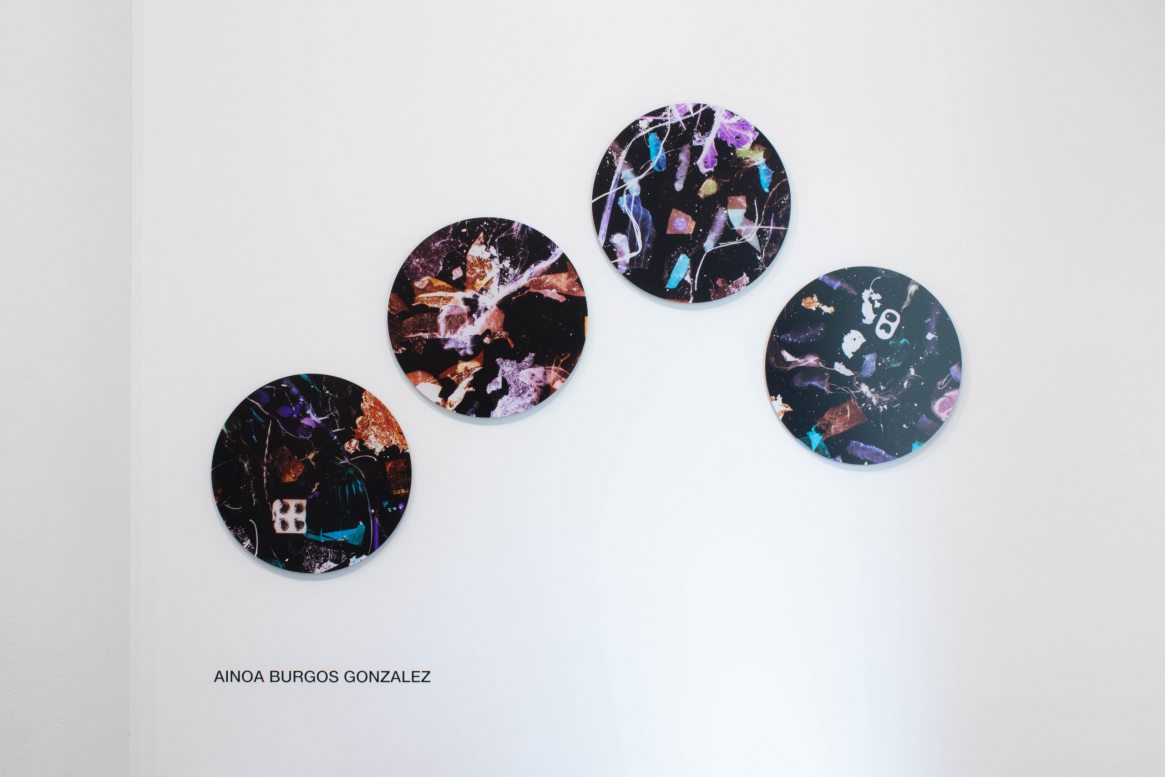

Optograms of the Earth, C-type Print, 490mm diameter (each print)

Disclosive

In On Photography, Susan Sontag describes two essentially different ways in which photography is practiced; ‘either as a lucid and precise act of knowing, of conscious intelligence, or as a pre-intellectual, intuitive mode of encounter. […] Both presuppose that photography provides a unique system of disclosures; that it shows us reality as we had not seen it before’. The work of this year’s postgraduate Photography students at the University of Brighton could be seen to emerge from, and to form, a series of dialogues between such acts of knowing and intuitive encounters. This show exhibits a selection of work from larger projects, each a result – or ongoing work in progress – of practice-based enquiry with photography as a principal research method. The MA Photography course acknowledges photography as an artistic medium using different technologies to explore as many ways of making photographs as possible. This year’s projects involve studio portraiture, constructed tableau, documentary, landscape, cityscape and still-life, realised in numerous ways, from established black and white and colour printing techniques to perhaps more unconventional photograms, transparencies and lumen prints. All projects understand how photographs make meaning, as much as what they might mean. While each project is distinctive, broad themes of human interactions and environmental encounters through photography unify the show.

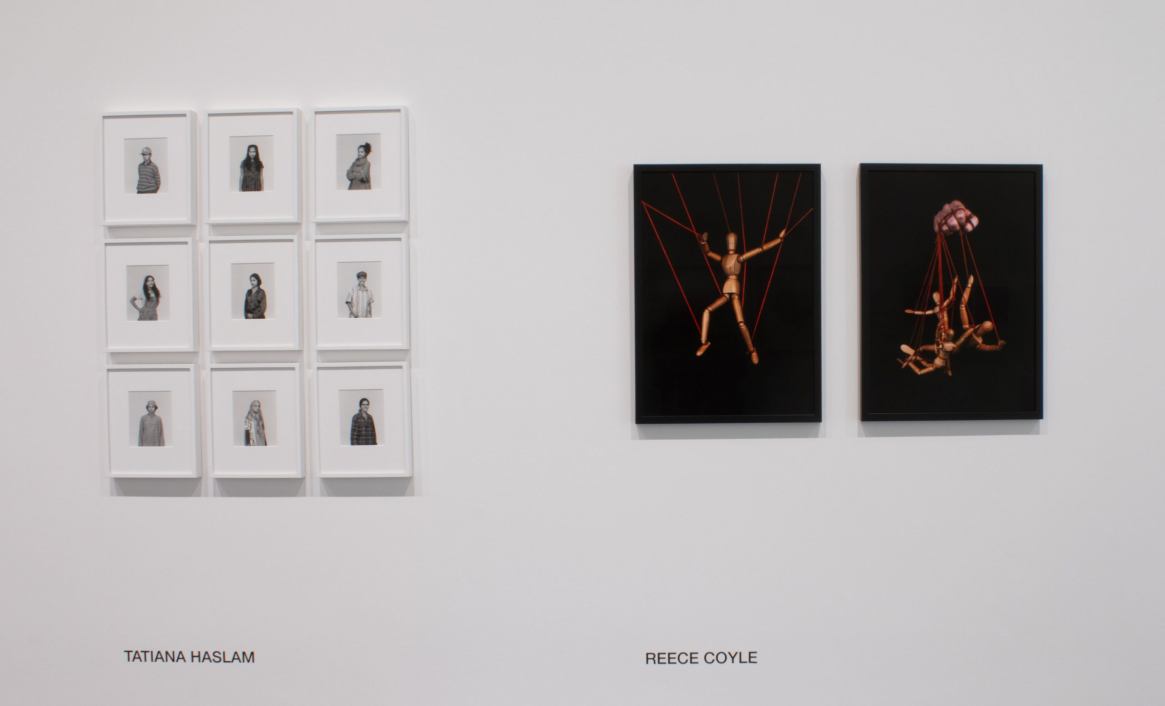

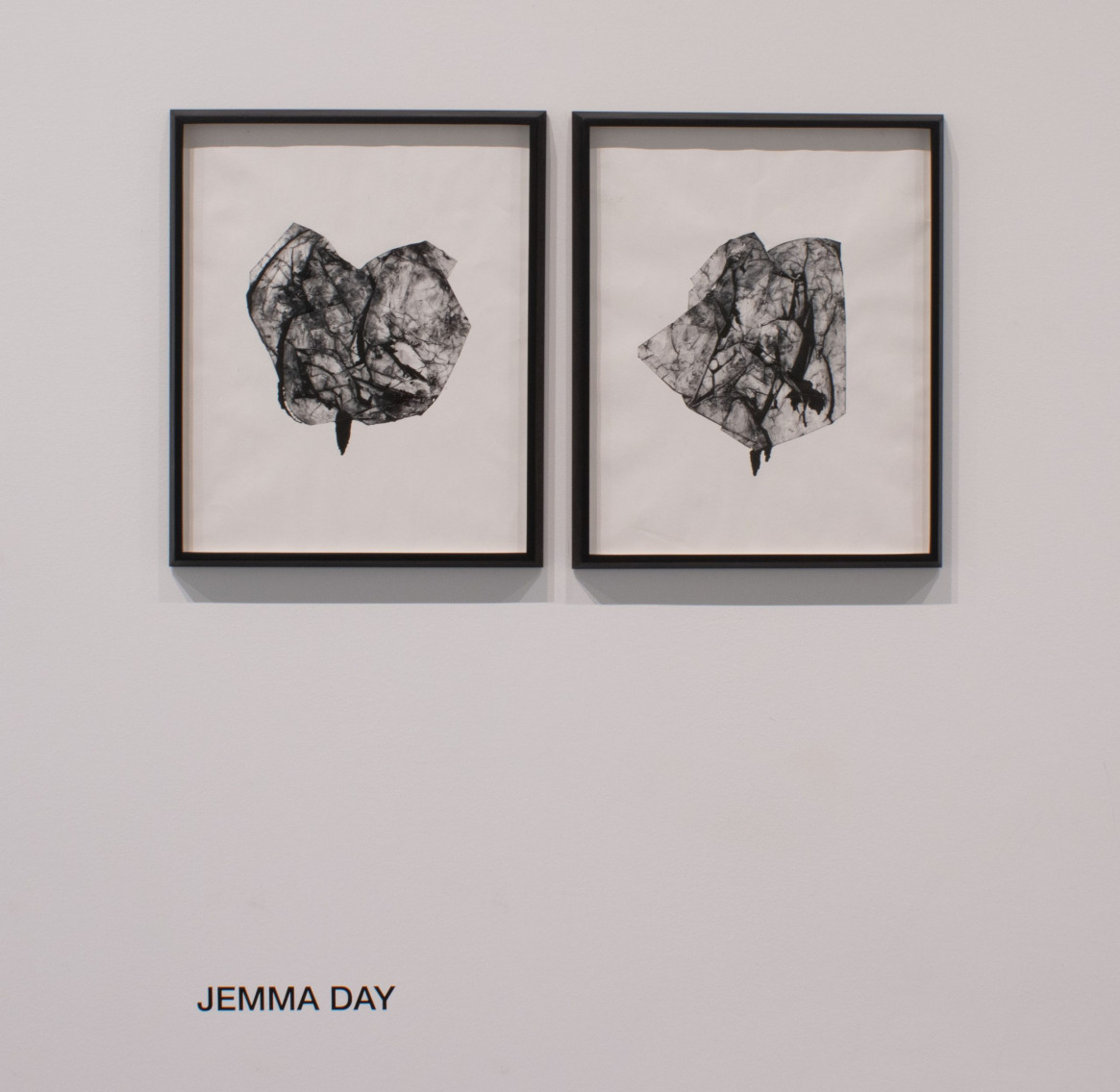

Of human interactions, Niloufar Arzani makes constructed pictures recreating incidental moments of estrangement between those otherwise in close proximity. James Kendall’s expressively figurative social documentary photographs celebrate collective social experience beyond generational stereotypes. Khazar Davaran draws upon combinations of ancient myth, remembered and observed encounters to picture modern human relationships. Michaela Lewis’s photographs closely observe the detailed gestures of touch in the everyday ritual of her father taking tea, while questioning the primacy of vision. Tatiana Haslam works in the photography studio to embody absent family through expression, gesture and pose in self-portraits. Reece Coyle’s constructed pictures symbolise human figures combining studio and montage techniques to address current socio-political themes. Jemma Day evokes the human body in sculptural and print works that explore questions of identity in reconfigured photographic material with renewed attention to light sensitivity and resemblance beyond representation.

Some works form connections between themes; Gurnoor Singh’s black and white photographs situate the image of the body of the photographer within complex urban architectural structures in varying degrees of presence, from reflection to shadow and silhouette. Sebastian Farron-Mahon’s colour photographs present chance encounters with and between strangers, complemented by overlooked city spaces, exploring the strangeness of ordinary modern places. Soham Joshi places photographic paper in the camera to make direct prints of architectural surfaces to explore questions of identity, difference and being.

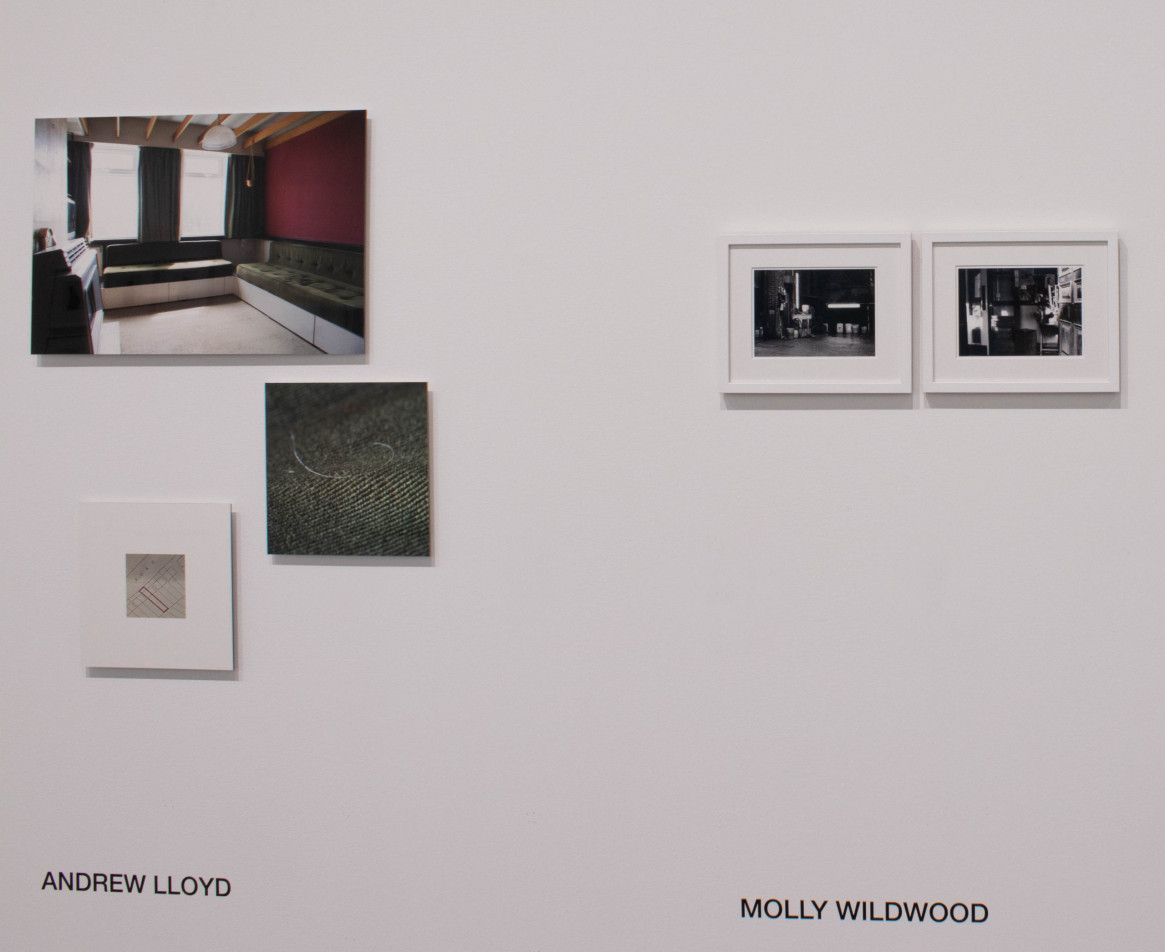

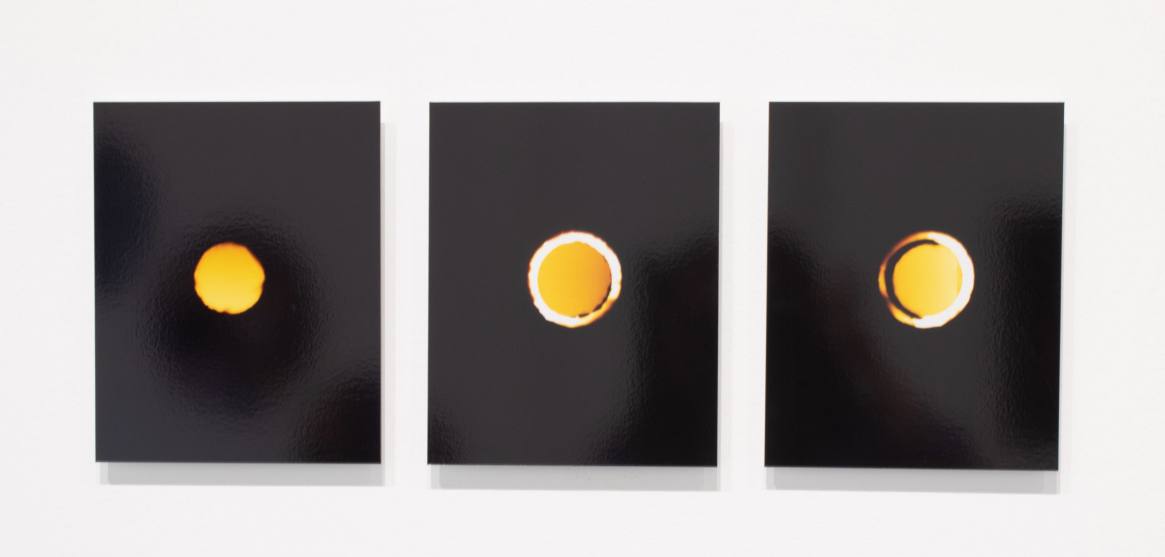

Among works with a focus on environmental encounters, Andrew Lloyd’s photographs show the interiors and details of a family home through the experience of bereavement; a house in the process of clearance is shown with the tools and fixtures by which it was made a home. From the domestic to the cosmic, Pranjali Jadhav works entirely in the colour darkroom to make pictures that evoke the original universal light source, through essential forms and associated colours produced exclusively with photographic processes. Ainoa Burgos Gonzalez’s colour photograms create images from the detritus of plastic waste and organic matter to offer detailed micro studies with which to reflect upon our current ecological situation. Susan Bell’s black and white photographs feature details of a riverbank, the surface of the water and fragments of plant forms to explore complex sensations and narrative associations with the natural world, the mixed joy and fear of potential submersion.

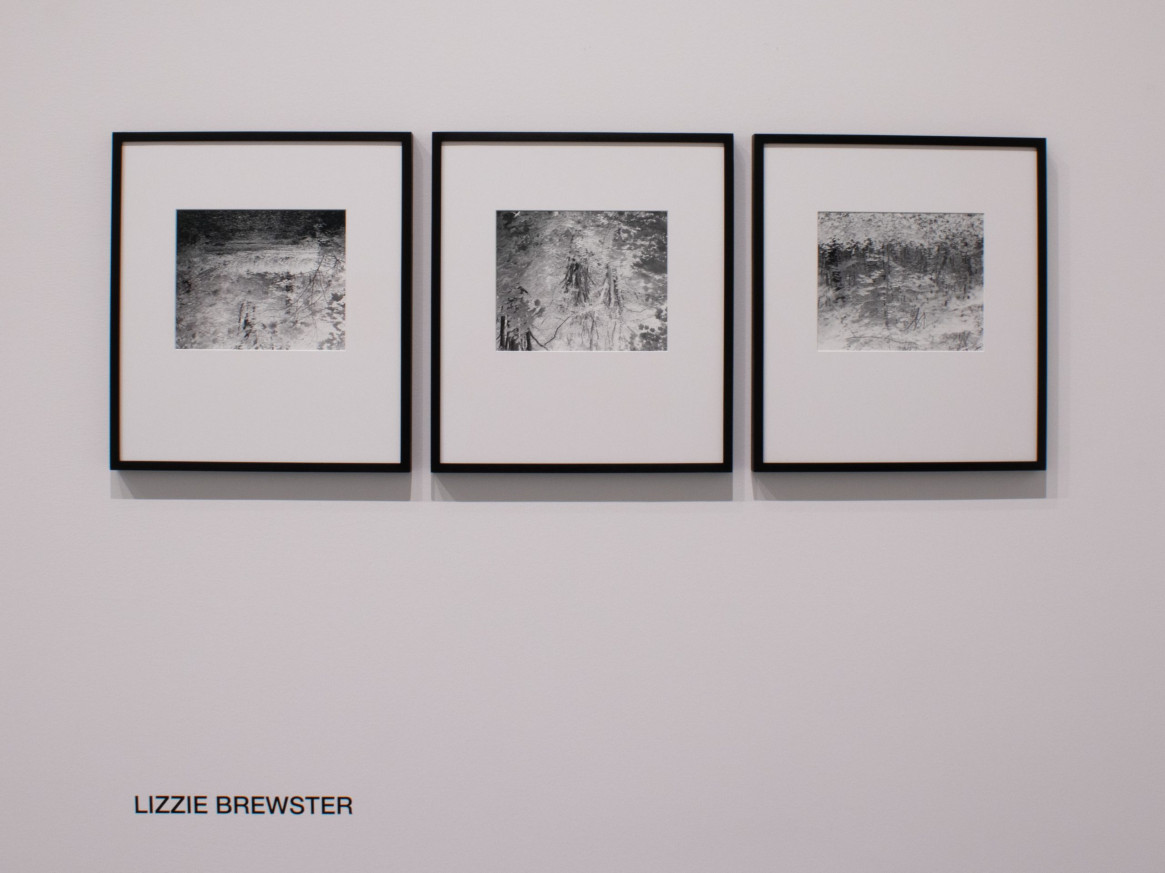

Lizzie Brewster’s black and white woodland photographs offer detailed descriptions of the outer world while evoking states of the inner mind stimulated by human encounters with nature. Yu-Chen Lee pictures fragments of cities and the natural world; recurrent shapes and effects of light associate the near and the elsewhere with notions of longing, migration and identity. Costanza Santilli’s black and white transparencies of aspects of the rural Sussex landscape, encountered by walks on and off its paths, comment upon photography itself, place and belonging. Giles Stokoe’s composite colour photography reveals the elaborate and constructed ways we see and reimagine the natural world beyond purely visual experiences and singular perspectives. Andrew Nutton’s colour photographs made from encounters within urban and rural places, form landscapes that put scientific measurement, artistic endeavour and history into dialogue with one another. Molly Wildwood’s black and white photographs make strange everyday architectural interiors, facades and details, defamiliarizing how we might see ordinarily experienced places.

Recalling Sontag’s earlier words, in all these works we are shown reality as not seen before in a kind of system of disclosures. In relation with thinking from photography’s early years, including Holmes and Eastlake, photography is attributed to the world. Eastlake, recently quoted by Silverman, wrote that the photograph is an emergent image; ‘one that approaches us from the future, and that arrives in the present’. The real value of photography is therefore less evidentiary than disclosive.