Introduction

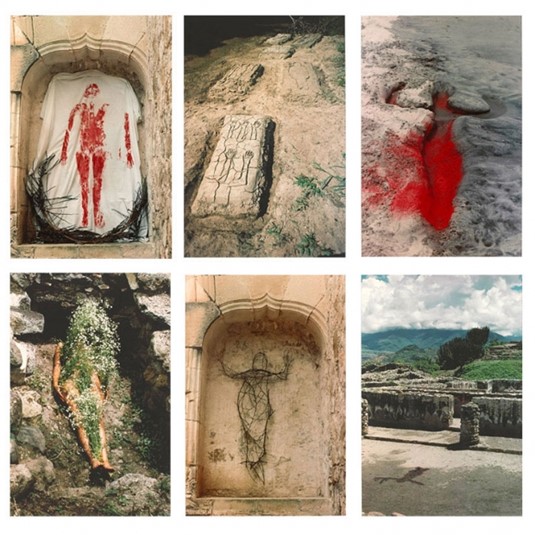

The symbiotic relationship between sculpture and photography has been growing since the beginning of the earliest practice. Indeed, this supportive and positive alliance helped and forced each artistic practice to grow and evolve. It is during 1970s that Photography became widely used by artists and hierarchies in art began to disappear. Along with this, during the 1970s Women Liberation Movement played a part and artists like Ana Mendieta, Eleanor Antin or Hannah Wilkie refigured their bodies in the spirit of Activism.1 Subsequently, with the help of photography the human body becomes a widely explored sculptural material. These mentioned artists, together with other contemporaries as for example Agnes Denes or Nancy Holt created a type of land art with photography as a tool that did not intend to dominate the landscape but to protect it and be reunited with it, therefore, producing pioneering environmental art (that has received relatively little attention from the Art critics.) These collaborative partnerships between Photography and Sculpture, Artists and Landscape can be analysed through the works of Mendieta, particularly Silueta Series (1973/81).

The symbiotic relationship between photography & Sculpture

Sculpture and Photography seems separated from an ontological barrier that divides the sculptural from the pictorial.2 However, Despite this existential boundary, through its history and stories Photography has not just documented sculptures but it has also helped to shape them and it has also extended the understanding of Sculpture. Indeed, “Relationship between sculpture and photography dates back to the younger medium invention.”3 Sculpture has always been an interesting theme to capture through the lens of the camera, and sculptural artworks were some of the first objects of desire to study. As identified by the Director of the Museum of Modern Art Glenn D. Lowry, “Since its birth in the first half of the 19th century, photography has offered extraordinary possibilities of documenting, interpreting and revaluating works of Art for both study and pleasure.”4

Foundational to this, is that during at least the last century the photographic medium has helped to shape the arts and find new languages that would have never existed without the invention of photography. In addition, an important point in the relationship between photography and sculpture in comparison with photography and painting is that between photography and sculpture there it seems to be less rivalry, both practices move around each other producing a beautiful and wide range of hybrids that in many occasions also involve other agents like Performance, Video, Painting… According to Tobia Bezzola in the text From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art “Photography has extended the history of Art to encompass the history of media.” After this Statement Bezzola adds: “If the gaze is limited to its bipolar interactions with classical sculpture, it will give us only a cropped, underexposed image of the phenomena involved.”5

Nonetheless, It is in the late 19th century when art theory first began to investigate this association between photography and sculpture and it is not by coincidence that the term ‘Photographism’ was coined by this time.6 ‘Photographisms’ are the “aesthetics perceptions generated by the photographic world view.”7 In other words, sculptors start to think about the photographic shot. The new ‘Photographisms’ perceptions began to interest the sculpture of the time and this concept keeps evolving beyond the 19th century. To illustrate how, Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973/81) is a perfect example to what degree the sculptural pieces are thought in an interaction with the camera. As seen in Figure 1, the sculptural work keeps in mind the camera angles and how is going to be seen through the lens. In fact, some of the works in this series can only be appreciated through the picture’s angle. It is a great example to demonstrate that sculpture is now richer in its own practice. Now, it can do more than carve, model or cast; now, it can photograph.8

In consequence, the perceptions of ‘Photographisms’ in the course of the 20th century are varied. Firstly, during art movements like Dada or Fluxus around 1957, the object gets hold of a privileged position in the art world. This happens indubitably with the help of the symbiotic relationship between photography and sculpture and how the object is portrayed through the lens. Afterwards, in the 1960s, beginning of the 1970s, and succeeding some artistic exercises of Marcel Duchamp like Tonsure (1921) Sculpture breaks its materiality and the object starts losing its imperialism. That is to say, it is no longer a symbol of permanence made in marble or bronze (for example). Sculpture and its materiality have changed and have become more ephemeral, using more impermanent materials. To break its strong materiality Sculpture gives an opportunity to concepts, processes and gestures as a communication tool for the practice. Therefore, sculpture starts to dematerialised.9 This dematerialisation of sculpture gives a new role to photography in the sculptural and art world, with many works existing primarily or uniquely in photographs (See Figure 1).

As an outcome of the evolution of this friendly union between photography and sculpture, in the 1970s Women Liberation Movement artists such as Wilikie, Holt, Antin, or Mendieta

reinterpreted, redefined and refigured their bodies in a form of activism,10 often using themselves as the centre of their statement, to present socio political issues.11 They use this sculptural-performative approach to communicate the psychological as well as the physical.12 The performance addressed by Mendieta, Dada or Fluxus relies clearly on photography or electronic production where its role it’s not merely documentary but constructive.13 This new vocabulary developed a different type of performance art, a performance for the camera. As depicted in Figure1, Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973/81) can be taken as a reference to explore the cooperative and intertwined evolution of both (photography and sculpture) and the wider and more contemporary understanding of sculpture. In this series of works she sculpted, filmed and photographed imprints of her body in nature, leaving a silhouette or a trace in the landscape.14 In Mendieta’s work Photography clearly does more than merely represent the three dimensional aspects of the piece.

The art critic Willoughby Sharp called to the use of the artists own body as an sculptural materials ‘Body Works’. Along with ‘Body Works’ comes the exploration of the ‘Rhetoric Pose’(a pose enacted for and mediated through the camera lens.)15 As Seen in Figure 1, Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973/81) is a brilliant example to portrait the ‘Rhetoric Pose’ in her ‘Body Works’. Likewise, other artists like Wilke, Dennis Oppenheim or more contemporary Carrie Mae also use this photographic artistic strategy for their ‘Body Works’. However, multidisciplinary artists like Mendieta or Oppenheim take the problematization of the aesthetic object in a different direction than Duchamp, who separated the concept from the object. This separation of object and concept brings new debates. On one hand ‘Rhetoric Pose’ works like Mendieta’s performances were exhibited in the expanded field, that is to say, outside the institutions of Modern Art Galleries. This fact of exhibiting artworks in ephemeral happenings in less objectified spaces than Art Galleries expands the concept ‘dematerialization of sculpture.’ On the other hand, it is debated if the photography becomes an art object.16 In addition to the study of ‘Body Works’ in the 1970s, it is worth saying that:

Photography of conceptual art did not need to be beautiful, unfamiliar or skilfully shot and printed […] often they looked like the work of amateurs photographers, this didn’t matter, for it was the absence of a sophisticated visual aesthetic that made photography a ground for the creation and communication of Plastic Art.17

Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973/81) Performances for the camera.

Mendieta’s multidisciplinary Silueta Series is a long time project produced from 1973 to 1981. In this prolific work she used her own naked body or a mould of her body, to mark her silhouette in a variety of landscapes. Mendieta’s happenings were mostly executed in Mexico and Iowa18 and were documented by herself or with the help of Hans Breder with a Super 8 film and 35mm slides.

In her Silueta Series Mendieta’s individual body is replaced or combined and transformed by fundamental materials such as earth, wood, gunpowder, water or mud to cast her own silhouettes, capturing this performative event with video and photography, often while it is being transformed.19 Initially, during her early works of this series (1972-1976) she used her personal physical body, as it can be seen in Figure 2: Image from Yagul, 1973. Afterwards, she began to create her ‘Body in Absentia’20 as it can be observed in Figure 3: Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (Fireworks piece), 1976. Mendieta used her diversity of ‘Body Works’ to portrait her own diaspora involving personal, cultural, language and political dislocation.21 She explores her Afro-Cuban roots with pre-Columbian rituals from Santería, icons like the Great Goddess Iconography,22 references to expatriations and other “ancient and indigenous civilisations of Africa, Asia, Central America and Europe that acknowledge the supernatural.”23 In addition, the female body is a pivotal thyme in Mendieta’s work, where she merges herself with natural and organic processes in the landscape. Nevertheless, Mendieta’s synergy with nature is never delivered through an aggressive interaction that scares the nature. Her work was personal even though it can be seen as representing Everywoman.24 This is because, among other concepts, her work is extremely feminine in so many ways, visually and conceptually. She persistently vocalise particular female issues in the 1970s (and beyond) due to the patriarchal society or patriarchal relationships with nature and the landscape. Then again, her work is extremely material, as it uses the primary elements of water, fire, earth and air but it is also extremely conceptual as it is about the primary concepts of time and history.25

To picture these concepts it can be taken as an example the first work of the series, Image from Yagul 1973 (See Figure 2). Mendieta appears, posing stiff, inside an ancient tomb in Oaxaca, Mexico. As it is depicted in the image, her naked body is covered by small daisy-like flowers looking like they are growing from her own body, becoming therefore one singular entity. “By posing herself in this situation the artist evokes the associations between life and death, the female body and nature.”26 “The art historian Judith Blocker affirms that with this metaphor Mendieta invests the female body with the very essence of nature.”27 That being said, this is only one example from a wide variety of works where Mendieta uses an array of metaphors and references to proclaim women’s organic relationship with nature.28

Equally important in Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973/81) is that the camera acts as a witness of the performative event. For Mendieta and for other artists of the time, the idea of intimacy is important, and with the camera they create a kind of private situation.29 Moreover, “In every instance, the performance has occurred, but witness primarily by the camera. We as viewers complete the situation as audience after a fact.”30 For example, Silueta Series (1973/81) also plays with the ephemerality of the work. The artworks are made to disappear, to vanish, in exception of the photographs and videos. She often produced works exclusively for the camera, providing the viewer with minimal information about the location, therefore constructing further narratives.31 The outcome is that the resulting images of this interaction have artistic function in their own right. However, there was still some tension among the art critics regarding whether the photographs are a document of the work or they were an art form in itself.32 Mendieta answered to this consideration herself in an interview with Dr. Joan Marter: “When you see a portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe you don’t say, ‘Well, is that a documentation of Georgia O’Keeffe or what is it?’ … I am refining nature in a different way. And the culture of working with nature, it is a different type of landscape work”33

She loosely defined her Silueta Series (1973/81) works as “sculptural interventions in the landscape that placed the physical body in relation with the environment.”34 In her interview with Marter, she contends that her works are both ‘body earthworks and photo.’35 Mendieta suggests that she enjoys slow interactions with art “I like a thing that can be digested. That’s the nice thing about art. You can go back and look at it again and again”36 This comment would clearly relate to her video and photography works. Then, she adds: “In Galleries and museums the Earths/body sculptures come to the viewer by way of photos, because of this and due to the impermanence of the sculptures the photographs become a very vital part of my work.”37Mendieta explained to Marter that the play between photography, her body and earth becomes somehow a ritual, and the photographs become traces of traces of the body.38 And it is due to this mix of medias that Genevieve Hyacinthe in her book Radical Virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and the Black Atlantic considers Mendieta’s work ‘Intermedia Endurance Works’ rather than ‘Ephemeral Works’ “because they transcend media categories and are postmodern artworks invigorated through audience interaction.”39

In spite of having hundreds of slides in her archives, usually only one is chosen as a photographic counterpart of the video and sculptural forms. Mendieta’s chosen images are usually tightly cropped and shoot directly above or in front of the subject, as it can be seen in Figure 2: Image from Yagul or in Figure 3: Anima, Silueta de Cohetes. In Mendieta’s body earthworks and photography the role of the camera is very important for its correct understanding, as the pieces are not made to be enjoyed on site. The camera applied a selective construction by the omission of elements that tell us about the attitudes and understandings of the represented.40 The images of these works do not portray much of the landscape or environment where they are made. Instead, they focus on the traces of the body, impeding to the viewer to have a proportion or scale and as mentioned before, constructing further narratives. The chromaticity of her works is also evolutive and relevant. During the first period of this series Mendieta used black and white photographs, moving to colour during the late 1970s. Together with this change came a restyling in her print’s sizes, becoming bigger to almost live-size, intentionally orchestrating the audience’s perceptions.41 As photography is not able to capture the erasure of the sculptural works like live performance of video can do, through the use of this media (photography) Mendieta enables further temporal elaboration, “freezing specific moments of time, which in turn lend her temporal sculptures a chronological validation and context that may otherwise be denied.”42

Political land art / Female earthworks

Furthermore, “It is important to recognise that colour, ethnicity, gender, nation and earth are all intertwined in Mendieta’s work”43 A powerful example to understand the multi-layered complexity of her works is Anima, Silueta de Cohetes. 1976, (See Figure 3).

Anima (roughly translated as ‘Soul’), Silueta de Cohetes (firework silhouette) was made in 1976 and it is considered one of the great artistic legacies of the post-war era.44 The piece is situated in the natural landscapes of Oaxaca, Mexico and recorded with a Super 8 film, from which Mendieta extracted still images. These still images are transferred to colour, higher definition, digital media still images in 2004 due to the publication and exhibition Ana Mendieta: Earth Body, Sculpture and Performance 1972-1985, organized by Olga Viso at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC45 and the dedicated efforts of the Estate of Ana Mendieta.46 The Figure 3 picture portrays a glowing fire, spirit like, silhouette sculpture in a frontal pose from the camera perspective. The arms are extended and bent upwards at the elbows, casting the Great Goddess Silhouette. This particular work from the Silueta Series (1973/81) resembles a bigger size figure than the 5foot tall of Mendieta’s body, and also, it is more generalised than other pieces and seems more androgynous. The armature holding the firecrackers is made of local cane and it was fabricated by a local artisan in Oaxaca, who also had knowledge of pyrotechnics.47 As it is usual in Mendieta’s works and in Art created during 1970s by Women Liberation Movement the materials and processes used are of high importance por the pieces communication, concept and meaning.

All these factors contribute to a deeper meaning. The symbology together with the orientation of the figure and the materials reflects in the Mexican tradition of burning ‘Castillos’ (Castles). In the folk tradition the free standing architectural ‘castles’ are made with locally sourced cane Carrizo, intertwined with firecrackers in a diversity of shapes and burned during myriad festivals. The most sumptuous ‘castles’ can be worn or carried for individuals participating in the festival.48 It is noticeable that Mendieta’s use of fire was a fascination. She uses fire in connection with burial traditions and rituals of passage and transformation. It was inspired not just by the ‘Castles’ but also from other Mexican traditions like lighting candles around graves during the vigil in the night of Día de los Muertos, or burning papier-mache Judas figures in Eastern festivities.49 This exploration of powerful traditions reveal the connection between Mendieta and folk customs, placing Mendieta as “an interlocutor between folk traditions and contemporary art.”50

As discussed before, in Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (1976) Mendieta makes use of the ‘Body in Absentia’, removing her physical self from the shoot. In conjunction to the ‘Body in Absentia’ there is also the ‘disappearance’ of the sculptural element caused by fire. In the context of this artwork, where the piece has been made by local artisans rather than a mass production firm, the disappearance has been related to the low and high labour dynamics of the creation. Mendieta’s executes a disappearance closer to the idea of the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard, disappearance as a socio-political act.51 In the same way, Hyacinthe expands the socio-historical context of Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (1976) by thinking of it as a monument honouring the indigenous and African lives lost in the United States. Hyacinthe considers that because of the year in which it was created, coinciding with the bicentennial anniversary of the US colonies in 1776 and the correspondent patriotic and imperialistic celebrations, where a variety of fireworks displays where arrayed.52 Although Mendieta never stated a direct link between the US bicentennial or the use of fireworks, in the same year lecture The Struggle for Culture Today is the Struggle for Life Mendieta expressed her concerns about the US aggression in the ‘Americas’.53

Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (1976) is an intense example of how Mendieta performed with the landscape for her sculptural photographs. From the analysis of Mendieta’s practice and her statements it is comprehensible that her understanding of Land Art differs from the practices of certain Land Art Practitioners of the time like Robert Smithson or Richard Serra. These artists made works exercising intrusive and destructive materials and procedures in unattainable natural locations.54 Conversely, Mendieta’s Earth-Body artworks never intended to remark technological and artistic innovation. Instead her practice addressed the ephemerality of the human being in the long history of the earth.55 As previously quoted and using her own words: “I am refining nature in a different way. And the culture of working with nature, it is a different type of landscape work.”56 While this is the case, in the 1970s it was not just Mendieta who had a different understanding of Land Art. Along this period other art practitioners like Holt, Denes, Judy Chicago or Carolee Schneemann were also pioneering the land art scene in a non-aggressive manner. In contrast to many of the high profile male contemporaries of Land Art. Yet, it is only now that we are “beginning to revisit some of the movement’s important predecessors, who were written off or purposely left out of this era simply because they were women.”57 Their work had a distinctive socio-political context, engagement and particular aesthetics. For Mendieta and her female contemporaries art is about how we look at the earth itself and doesn’t have the intention of leaving the mark of the artist upon it. They are the pioneers of what today is called environmental art. After all, the renowned art historian and curator Peter Selz considers Dene’s piece in Sullivan County Rice/Tree/Burial (1968) the “first large scale site-specific piece anywhere with ecological concerns.”58 Mendieta takes this bond with nature more personally stating that:

I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source.59

Even though, their practices are very different, even opposite to each other in concepts and procedures, they all have something in common, and this is the use of photography. All of the 1970s Land Artists were using photography as a vital part of their work and for all of them the resulting photographic register of their performative events with the landscape will be the world wide representation of their artworks. For example, Antin’s work 100 boots (1971-73) became a worldwide postcard phenomena thanks to a deeper connection with photography. Although, there were many explorations with the landscape, the body and photography, there are not many artists know to have had such a close relationship with the medium as Ana Mendieta.

Conclusion:

It has been shown that the symbiotic relationship between sculpture and photography brings new and previously unimaginable forms of art. This avant-garde forms of art are hybrids born by the understanding of a wider creative practice, where Sculpture dematerialize and Photography spread its wings. The ‘Photographisms’ arising from the fusion and understanding between practices brings to the light works like Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series (1973/81). Through the ‘Rhetoric Pose’, photography and the ‘Body Absentia’ Mendieta’s ‘Body Earthworks and Photo’ works present to the public more complex concepts about the exchange of art, photography, humanity and nature. Simultaneously to other female artists part of the Women Liberation Movement of the 1970s Mendieta produced a new language in understanding with nature, hence pioneering strong contemporary art currents like environmental art. Today, when the artworld is rereading their works and studying them with the impetus that is deserved, they become so relevant for art and the world in which we live. Perhaps, if art historians, art academy and art critics of the time had recognise, accept and advocate these artists and artworks to the common knowledge, today, we would have a different relationship and understanding of nature, art, sculpture and photography.

Footnotes

1 Roxana Marcoci, “X. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object,” The Original Copy, ed. David Frankel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 220.

2 Tobia Bezzola, “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art,” The Original Copy, ed. David Frankel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 28.

3 Glenn D. Lowry, “Foreword,” The Original Copy, ed. David Frankel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 7.

4 Lowry, “Foreword,” 7.

5 Bezzola, “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art,” 28.

6 Bezzola, “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art,” 29.

7 J. A. Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth, “Photographismen in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts,” Malerei und Photographie im Dialog, ed. Erika Billeter (Zurich: Benteli Verlag, 1977), 321-28.

8 Bezzola, “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art,” 28.

9 Bezzola, “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art,” 33.

10 Marcoci, “X. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object,” 220.

11 Susan Butler, interview with Tory Arefin and Maureen O.Paley, “Performing for the Camera” Photography as Performance: Message through object and Picture, ed. The Photographers Gallery, (London: The Photographers Gallery, 1986), 15.

12 Susan Butler, interview with Tory Arefin and Maureen O.Paley, “Performing for the Camera” Photography as Performance: Message through object and Picture, ed. The Photographers Gallery, (London: The Photographers Gallery, 1986), 15.

13 Marcoci, “X. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object,” 219

14 Anna McNay, “Ana Mendieta: Photography, Films and The Silueta Series.” Photomonitor, October 2013.

15 Marcoci, “X. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object,” 219

16 Gill Perry, “The Expanded Field: Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series,” Frameworks for Modern Art, ed. Jason Gaiger (New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Open University, 2003), 158.

17 Bezzola, “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art,” 34.

18 Gill Perry, “The Expanded Field: Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series,” 153

19 Mary Sabbatino, “Ana Menditeta: Identity and the Situeta Series,” Ana Mendieta, ed. Gloria Moure (Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa and Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, 1996), 136.

20 Genevive Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic (Massachusetts: Institute of Technology, 2019), 18.

21 Howard Oransky, “Foreword” Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta, ed. Lynn Lukkas and Howard Oransky (Minneapolis: Katherine E. Nash Gallery, University of Minnesota and University of California Press, 2015), 9-11.

22 R. Lippard, “Introduction” Who is Ana Mendieta?, ed. Christine Redfern and Caro Caron (New York: The Feminist Press, 2011,) 13.

23 Christine Redfern, Who is Ana Mendieta? (New York: The Feminist Press, 2011,) 32.

24 Lucy R. Lippard, “Introduction” Who is Ana Mendieta?, 8.

25 Gloria Moure, “Ana Mendieta,” Ana Mendieta, ed. Gloria Moure (Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa and Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, 1996,) 13.

26 Gill Perry, “The Expanded Field: Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series,” 172.

27 Jane Blocker, Where is Ana Mendieta? Identity, Performativity, and Exile (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999,) 65.

28 Gill Perry, “The Expanded Field: Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series,” 172.

29 Susan Butler, interview with Tory Arefin and Maureen O.Paley, “Performing for the Camera,” 8.

30 Susan Butler, interview with Tory Arefin and Maureen O.Paley, “Performing for the Camera,” 7.

31 Susan Butler, interview with Tory Arefin and Maureen O.Paley, “Performing for the Camera,” 13.

32 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 71.

33 Joan Marter, “1 February 1985: Joan Marter and Ana Mendieta” Ana Mendieta, Traces, ed. Adrian Heathfield (London: Hayward Publishing, 2013,) 229-230.

34 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 71.

35 McNay, “Ana Mendieta: Photography, Films and The Silueta Series.”

36 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 61.

37 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 71.

38 Joan Marter, “1 February 1985: Joan Marter and Ana Mendieta,” 229-230.

39 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 18.

40 Roxana Marcoci, “V. Marcel Duchamp’s Box in a Valise: The Ready Made as Reproduction” The Original Copy, ed. David Frankel (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 114.

41 McNay, “Ana Mendieta: Photography, Films and The Silueta Series.”

42 Colette Chattopadhyay, “Ana Mendieta’s Sphere of Influence,” Sculpture, 18.5 (1999): 34-41

43 Blocker, Where is Ana Mendieta? Identity, Performativity, and Exile, 63.

44 Howard Oransky, “Covered in Time and History: the Films of Ana Mendieta” Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta, ed. Lynn Lukkas and Howard Oransky (Minneapolis: Katherine E. Nash Gallery, University of Minnesota and University of California Press, 2015) 9-11.

45 Olga M. Viso, Ana Mendieta: Earth Body: Sculpture and Performance, 1972-1985 (Washington DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution,2004) 7.

46 Howard Oransky, “Foreword,” 11

47 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 62.

48 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 62.

49 Olga Viso, Unseen Mendieta: The Unpublished Works of Ana Mendieta (Munich, Berlin, London, New York: Prestel Verlag, 2008) 153.

50 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 62.

51 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 62.

52 Hyacinthe, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic, 63.

53 Ana Mendieta, “Ana Mendieta. Personal Writings: The Struggle for Culture Today is the Struggle for Life” Ana Mendieta, ed. Gloria Moure. (Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa and Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, 1996,) 171-176.

54 John Haber, “Down to Earth”, Art Reviews from Around New York, (New York: Haber Arts, July 2008)

55 Anabel Roque Rodriguez, Ana Mendieta – An Artwork As a Dialogue Between the Landscape and the Female Body, Widewalls Magazine, Jan. 2016.

56 Linda Montano, “An Interview with Ana Mendieta”, Performance Artist Talking in the Eighties, ed. Lidia M. Montano, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000,) 394-398

57 Megan O’Grady, “Women Land Artists Get Their Day in the Museum” New York Times Style Magazine, New York Times, Nov. 2018.

58 Agnes Denes, Agnes Denes, Agnes Denes Studio [n.d].

59 Susan Best, “Ana Mendieta, Connecting to Earth,” Exhibition Archive, Ana Mendieta, Institute of Modern Art, 2019

Bibliography

Bate, David. Art Photography. London: Tate Enterprises Ltd., 2015. Print.

Best, Susan. “Ana Mendieta, Connecting to Earth.” Exhibition Archive, Ana Mendieta. Institute of Modern Art. 2019. Web. 18 Dec 2021. https://ima.org.au/exhibitions/ana-mendieta-connecting-to-the-earth/

Bezzola, Tobia. “From Sculpture in Photography to Photography as Plastic Art.” The Original Copy. Ed. David Frankel. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Print.

Blocker, Jane. Where is Ana Mendieta? Identity, Performativity, and Exile. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1999. Print.

Butler, Susan. interview with Tory Arefin and Maureen O.Paley. “Performing for the Camera.” Photography as Performance: Message through object and Picture. Ed. The Photographers Gallery. London: The Photographers Gallery, 1986. Print.

Chattopadhyay, Colette. “Ana Mendieta’s Sphere of Influence.” Sculpture 18.5 (1999): 34-41. Web. 18 Dec. 2021. https://web-p-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.brighton.ac.uk/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=2a2f0872-7858-461c-ae5f-44b570dbdbd8%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=505813661&db=aft

Denes, Agnes. Agnes Denes. Agnes Denes Studio. [n.d] Web. 4 Jan. 2022 http://www.agnesdenesstudio.com/index.html

Haber, John. “Down to Earth.” Art Reviews from Around New York. New York: Haber Arts, July 2008. Web. 19 Dec. 2021 https://www.haberarts.com/decoys.htm

Hyacinthe, Genevive, Radical virtuosity: Ana Mendieta and The Black Atlantic. Massachusetts: Institute of Technology, 2019. Print.

Lippard, Lucy R. “Introduction” Who is Ana Mendieta? Ed. Christine Redfern and Caro Caron. New York: The Feminist Press, 2011. Print.

Lowry, Glenn D. “Foreword.” The Performing Body as Sculptural Object.” The Original Copy. Ed. David Frankel. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Print.

Marcoci ,Roxana. “V. Marcel Duchamp’s Box in a Valise: The Ready Made as Reproduction” The Original Copy. Ed. David Frankel. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Print.

Marcoci ,Roxana. “X. The Performing Body as Sculptural Object.” The Original Copy. Ed. David Frankel. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010. Print.

Marter, Joan. “1 February 1985: Joan Marter and Ana Mendieta.” Ana Mendieta, Traces. Ed. Adrian Heathfield. London: Hayward Publishing, 2013. Print.

McNay, Anna. “Ana Mendieta: Photography, Films and The Silueta Series.” Photomonitor. October 2013. Web. 15 Dec.2021. https://photomonitor.co.uk/essay/photography-film-and-the-silueta-series/

Mendieta, Ana. “Ana Mendieta. Personal Writings: The Struggle for Culture Today is the Struggle for Life” Ana Mendieta. Ed. Gloria Moure. Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa and Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, 1996. Print.

Montano, Lidia. “An Interview with Ana Mendieta.” Performance Artist Talking in the Eighties. Ed. Lidia M. Montano. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. Print.

Moure, Gloria. “Ana Mendieta.” Ana Mendieta. Ed. Gloria Moure. Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa and Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, 1996. Print.

O’Grady, Megan. “Women Land Artists Get Their Day in the Museum.” New York Times Style Magazine. New York Times. Nov. 2018. Web. 23 Dec 2021.

Oransky, Howard. “Covered in Time and History: the Films of Ana Mendieta” Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta. Ed. Lynn Lukkas and Howard Oransky. Minneapolis: Katherine E. Nash Gallery – University of Minnesota and University of California Press, 2015. Print.

Oransky, Howard. “Foreword” Covered in Time and History: The Films of Ana Mendieta. Ed. Lynn Lukkas and Howard Oransky. Minneapolis: Katherine E. Nash Gallery – University of Minnesota and University of California Press, 2015. Print.

Peery, Gill. “The Expanded Field: Ana Mendieta’s Silueta Series.” Frameworks for Modern Art. Ed. Jason Gaiger. New Haven and London: Yale University Press in association with The Open University, 2003. Print.

Reason, Matthew. Documentation, Disappearance and the Representation of Live Performance. Hampshire and New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006. Print

Redfern, Christine. Who is Ana Mendieta? New York: The Feminist Press, 2011. Print.

Roque Rodriguez, Anabel. Ana Mendieta – An Artwork As a Dialogue Between the Landscape and the Female Body. Widewalls Magazine, Jan. 2016. Web. 20 Dec 2021. https://www.widewalls.ch/magazine/ana-mendieta-landscape-female-body

Sabbatino, Mary. “Ana Menditeta: Identity and the Situeta Series.” Ana Mendieta. Ed. Gloria Moure. Barcelona: Ediciones Poligrafa and Centro Galego de Arte Contemporanea, 1996. Print.

Shmoll, J. A gen. Eisenwert. “Photographismen in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts.“ Malerei und Photographie im Dialog. Ed. Erika Billeter. Zurich: Benteli Verlag, 1977. Print

Viso, Olga M. Ana Mendieta: Earth Body: Sculpture and Performance, 1972-1985. Washington DC: Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, 2004. Print.

Viso, Olga M. Unseen Mendieta: The Unpublished Works of Ana Mendieta. Munich, Berlin, London, New York: Prestel Verlag, 2008. Print.

Images References:

Figure 1: Ana Mendieta. Silueta Series. 1973/81-1991. Body earthworks and photo, Pigmented Inkjet prints. 508 x 337mm. Institute of Contemporary Art Boston. 13 Jan. 2022. https://www.icaboston.org/art/ana-mendieta/silueta-works-mexico#related-exhibition

Figure 2: Silueta Series (Image from Yagul), 1973. Body Earthworks and Photo. Digitalized image. The Estate of Ana Mendieta. 13 Jan. 2022. https://www.anamendietaartist.com/work/67f45e26-9b6f-4358-92d8-01f3c4091410-xsyhr-lgr36/67f45e26-9b6f-4358-92d8-01f3c4091410-xsyhr-lgr36/67f45e26-9b6f-4358-92d8-01f3c4091410-xsyhr-lgr36

Figure 3: Silueta de Cohetes (Firework Piece), 1976. Body Earthworks and Photo. Digitalized image. The Estate of Ana Mendieta. 13 Jan. 2022. https://www.anamendietaartist.com/work/67f45e26-9b6f-4358-92d8-01f3c4091410-xsyhr-lgr36/67f45e26-9b6f-4358-92d8-01f3c4091410-xsyhr-lgr36/67f45e26-9b6f-4358-92d8-01f3c4091410-xsyhr-lgr36